Approved July 2017

International Association of Assessing Officers

IAAO assessment standards represent a consensus in the assessing profession and have been adopted by the Board of

Directors of IAAO. The objective of IAAO standards is to provide a systematic means for assessing officers to improve and

standardize the operation of their offices. IAAO standards are advisory in nature and the use of, or compliance with, such

standards is voluntary. If any portion of these standards is found to be in conflict with national, state, or provincial laws,

such laws shall govern. Ethical and/or professional requirements within the jurisdiction may also take precedence over

technical standards. – February 2022

Standard on

Mass Appraisal

of Real Property

Acknowledgments

At the me of the 2018 rewrite of this standard, the Technical Standards Commiee was comprised of Alan Dornfest, AAS

(Chair), Albert Marchand, Josh Myers, Wayne Forde, August Debarn, Carol Neihardt, Pat O'Conner, and Larry Clark, IAAO

Sta Liaison.

Revision notes

This standard replaces the April 2013 Standard on Mass Appraisal of Real Property and is a complete revision. The 2013

Standard on Mass Appraisal of Real Property was a paral revision that replaced the 2012 standard, which replaced the

2002 standard. The 2002 standard combined and replaced the 1983 Standard on the Applicaon of the Three Approaches to

Value in Mass Appraisal, the 1984 Standard on Mass Appraisal, and the 1988 Standard on Urban Land Valuaon.

Published by

International Association of Assessing Officers

314 W 10th St.

Kansas City, Missouri 64105-1616

816-701-8100

Fax: 816-701-8149

www.iaao.org

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: ISBN 978-0-88329-248-8

Copyright © 2019 by the International Association of Assessing Officers

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form, in an electronic retrieval system or otherwise, without

the prior written permission of the publisher. IAAO grants permission for copies to be made for educational use as

long as (1) copies are distributed at or below cost, (2) IAAO is identified as the publisher, and (3) proper notice of

the copyright is affixed.

Produced in the United States of America.

Contents

1 Scope .................................................................................................................1

2. Introduction .......................................................................................................1

3. Collecting and Maintaining Property Data .........................................................1

3.1 Overview ....................................................................................................1

3.2 Geographic Data.........................................................................................1

3.3 Property Characteristics Data.....................................................................2

3.3.1 Selection of Property Characteristics Data .............................................2

3.3.2 Data Collection .......................................................................................3

3.3.2.1 Initial Data Collection ..................................................................3

3.3.2.2 Data Collection Format ...............................................................3

3.3.2.3 Data Collection Manuals .............................................................3

3.3.2.4 Data Accuracy Standards ............................................................3

3.3.2.5 Data Collection Quality Control ..................................................4

3.3.3 Data Entry ..............................................................................................4

3.3.4 Maintaining Property Characteristics Data ............................................4

3.3.5 Alternative to Periodic On-Site Inspections ...........................................5

3.4 Sales Data ...................................................................................................5

3.5 Income and Expense Data ..........................................................................5

3.6 Cost and Depreciation Data .......................................................................5

4. Valuation ........................................................................................................6

4.1 Valuation Models .......................................................................................6

4.2 The Cost Approach .....................................................................................6

4.3 The Sales Comparison Approach ................................................................7

4.4 The Income Approach ................................................................................7

4.5 Land Valuation ...........................................................................................8

4.6 Considerations by Property Type ...............................................................8

4.6.1 Single-Family Residential Property .........................................................8

4.6.2 Manufactured Housing ..........................................................................8

4.6.3 Multifamily Residential Property ...........................................................9

4.6.4 Commercial and Industrial Property ......................................................9

4.6.5 Nonagricultural Land ..............................................................................9

4.6.6 Agricultural Property ..............................................................................9

4.6.7 Special-Purpose Property .......................................................................9

4.7 Value Reconciliation ...................................................................................9

4.8 Frequency of Reappraisals .........................................................................9

5. Model Testing, Quality Assurance, and Value Defense ....................................10

5.1 Model Diagnostics ....................................................................................10

5.2 Sales Ratio Analyses .................................................................................10

5.2.1 Assessment Level .................................................................................10

5.2.2 Assessment Uniformity ........................................................................10

5.3 Holdout Samples ......................................................................................11

5.4 Documentation ........................................................................................12

5.5 Value Defense ..........................................................................................12

6. Managerial and Space Considerations .............................................................12

6.1 Overview ..................................................................................................12

6.2 Staffing and Space ....................................................................................12

i

STANDARD ON MASS APPRAISAL OF REAL PROPERTY—2017

iv

6.2.1 Staffing ......................................................................................................13

6.2.2 Space Considerations ...........................................................................13

6.3 Data Processing Support ..........................................................................13

6.3.1 Hardware .............................................................................................13

6.3.2 Software ...............................................................................................13

6.3.2.1 Custom Software ......................................................................14

6.3.2.2 Generic Software ......................................................................14

6.4 Contracting for Appraisal Services ...........................................................15

6.5 Benefit-Cost Considerations .....................................................................15

6.5.1 Overview ..............................................................................................15

6.5.2 Policy Issues .........................................................................................15

6.5.3 Administrative Issues ...........................................................................15

7. Reference Materials .........................................................................................15

7.1 Standards of Practice ...............................................................................15

7.2 Professional Library ..................................................................................15

References ............................................................................................................16

Suggested Reading ................................................................................................16

ii

1

STANDARD ON MASS APPRAISAL OF REAL PROPERTY—2017

Standard on Mass Appraisal of Real Property

1. Scope

This standard defines requirements for the mass appraisal of real property. The primary focus is on mass appraisal for ad

valorem tax purposes. However, the principles defined here should also be relevant to CAMAs (CAMAs) (or automated

valuation models) used for other purposes, such as mortgage portfolio management. The standard primarily addresses the

needs of the assessor, assessment oversight agencies, and taxpayers.

This standard addresses mass appraisal procedures by which the fee simple interest in property can be appraised at mar-

ket value, including mass appraisal application of the three traditional approaches to value (cost, sales comparison, and

income). Single-property appraisals, partial interest appraisals, and appraisals made on an other-than-market-value basis

are outside the scope of this standard. Nor does this standard provide guidance on determining assessed values that differ

from market value because of statutory constraints such as use value, classification, or assessment increase limitations.

Mass appraisal requires complete and accurate data, effective valuation models, and proper management of resources.

Section 2 introduces mass appraisal. Section 3 focuses on the collection and maintenance of property data. Section 4

summarizes the primary considerations in valuation methods, including the role of the three approaches to value in the

mass appraisal of various types of property. Section 5 addresses model testing and quality assurance. Section 6 discusses

certain managerial considerations: staff levels, data processing support, contracting for reappraisals, benefit-cost issues,

and space requirements. Section 7 discusses reference materials.

2. Introduction

Market value for assessment purposes is generally determined through the application of mass appraisal techniques. Mass

appraisal is the process of valuing a group of properties as of a given date and using common data, standardized methods,

and statistical testing. To determine a parcel’s value, assessing officers must rely upon valuation equations, tables, and

schedules developed through mathematical analysis of market data. Values for individual parcels should not be based

solely on the sale price of a property; rather, valuation schedules and models should be consistently applied to property

data that are correct, complete, and up-to-date.

Properly administered, the development, construction, and use of a CAMA system results in a valuation system character-

ized by accuracy, uniformity, equity, reliability, and low per-parcel costs. Except for unique properties, individual analyses

and appraisals of properties are not practical for ad valorem tax purposes.

3. Collecting and Maintaining Property Data

The accuracy of values depends first and foremost on the completeness and accuracy of property characteristics and market

data. Assessors will want to ensure that their CAMA systems provide for the collection and maintenance of relevant land,

improvement, and location features. These data must also be accurately and consistently collected. The CAMA system

must also provide for the storage and processing of relevant sales, cost, and income and expense data.

3.1 Overview

Uniform and accurate valuation of property requires correct, complete, and up-to-date property data. Assessing offices

must establish effective procedures for collecting and maintaining property data (i.e., property ownership, location, size,

use, physical characteristics, sales price, rents, costs, and operating expenses). Such data are also used for performance

audits, defense of appeals, public relations, and management information. The following sections recommend procedures

for collecting these data.

3.2 Geographic Data

Assessors should maintain accurate, up-to-date cadastral maps (also known as assessment maps, tax maps, parcel boundary

maps, and property ownership maps) covering the entire jurisdiction with a unique identification number for each parcel.

Such cadastral maps allow assessing officers to identify and locate all parcels, both in the field and in the office. Maps

become especially valuable in the mass appraisal process when a geographic information system (GIS) is used. A GIS

permits graphic displays of sale prices, assessed values, inspection dates, work assignments, land uses, and much more.

In addition, a GIS permits high-level analysis of nearby sales, neighborhoods, and market trends; when linked to a CAMA

STANDARD ON MASS APPRAISAL OF REAL PROPERTY—2017

2

system, the results can be very useful. For additional information on cadastral maps, parcel identification systems, and

GIS, see the Standard on Manual Cadastral Maps and Parcel Identifiers (IAAO 2016b), Standard on Digital Cadastral

Maps and Parcel Identifiers (IAAO 2015), Procedures and Standards for a Multipurpose Cadastre (National Research

Council 1983), and GIS Guidelines for Assessors (URISA and IAAO 1999).

3.3 Property Characteristics Data

The assessor should collect and maintain property characteristics data sufficient for classification, valuation, and other

purposes. Accurate valuation of real property by any method requires descriptions of land and building characteristics.

3.3.1 Selection of Property Characteristics Data

Property characteristics to be collected and maintained should be based on the following:

• Factors that influence the market in the locale in question

• Requirements of the valuation methods that will be employed

• Requirements of classification and property tax policy

• Requirements of other governmental and private users

• Marginal benefits and costs of collecting and maintaining each property characteristic

Determining what data on property characteristics to collect and maintain for a CAMA system is a crucial decision with

long-term consequences. A pilot program is one means of evaluating the benefits and costs of collecting and maintaining

a particular set of property characteristics (see Gloudemans and Almy 2011, 46–49). In addition, much can be learned

from studying the data used in successful CAMAs in other jurisdictions. Data collection and maintenance are usually the

costliest aspects of a CAMA. Collecting data that are of little importance in the assessment process should be avoided

unless another governmental or private need is clearly demonstrated.

The quantity and quality of existing data should be reviewed. If the data are sparse and unreliable, a major recanvass will

be necessary. Data that have been confirmed to be reliable should be used whenever possible. New valuation programs or

enhancements requiring major recanvass activity or conversions to new coding formats should be viewed with suspicion

when the existing database already contains most major property characteristics and is of generally good quality.

The following property characteristics are usually important in predicting residential property values:

Improvement Data

• Living area

• Construction quality or key components thereof (foundation, exterior wall type, and the like)

• Effective age or condition

• Building design or style

• Secondary areas including basements, garages, covered porches, and balconies

• Building features such as bathrooms and central air-conditioning

• Significant detached structures including guest houses, boat houses, and barns

Land Data

• Lot size

• Available utilities (sewer, water, electricity)

Location Data

• Market area

• Submarket area or neighborhood

• Site amenities, especially view and golf course or water frontage

• External nuisances, (e.g., heavy traffic, airport noise, or proximity to commercial uses).

3

STANDARD ON MASS APPRAISAL OF REAL PROPERTY—2017

For a discussion of property characteristics important for various commercial property types, see Fundamentals of Mass

Appraisal (Gloudemans and Almy 2011, chapter 9).

3.3.2 Data Collection

Collecting property characteristics data is a critical and expensive phase of reappraisal. A successful data collection program

requires clear and standard coding and careful monitoring through a quality control program. The development and use

of a data collection manual is essential to achieving accurate and consistent data collection. The data collection program

should result in complete and accurate data.

3.3.2.1 Initial Data Collection

A physical inspection is necessary to obtain initial property characteristics data. This inspection can be performed either

by appraisers or by specially trained data collectors. In a joint approach, experienced appraisers make key subjective deci-

sions, such as the assignment of construction quality class or grade, and data collectors gather all other details. Depending

on the data required, an interior inspection might be necessary. At a minimum, a comprehensive exterior inspection should

be conducted. Measurement is an important part of data collection.

3.3.2.2 Data Collection Format

Data should be collected in a prescribed format designed to facilitate both the collecting of data in the field and the entry

of the data into the computer system.

A logical arrangement of the collection format makes data collection easier. For example, all items requiring an interior

inspection should be grouped together. The coding of data should be as objective as possible, with measurements, counts,

and check-off items used in preference to items requiring subjective evaluations (such as “number of plumbing fixtures”

versus “adequacy of plumbing: poor, average, good”). With respect to check-off items, the available codes should be exhaus-

tive and mutually exclusive, so that exactly one code logically pertains to each observable variation of a building feature

(such as structure or roof type). The data collection format should promote consistency among data collectors, be clear and

easy to use, and be adaptable to virtually all types of construction. Specialized data collection formats may be necessary

to collect information on agricultural property, timberland, commercial and industrial parcels, and other property types.

3.3.2.3 Data Collection Manuals

A clear, thorough, and precise data collection manual is essential and should be developed, updated, and maintained.

The written manual should explain how to collect and record each data item. Pictures, examples, and illustrations are

particularly helpful. The manual should be simple yet complete. Data collection staff should be trained in the use of the

manual and related updates to maintain consistency. The manual should include guidelines for personal conduct during

field inspections, and if interior data are required, the manual should outline procedures to be followed when the property

owner has denied access or when entry might be risky.

3.3.2.4 Data Accuracy Standards

The following standards of accuracy for data collection are recommended.

• Continuous or area measurement data, such as living area and exterior wall height, should be accurate within 1 foot

(rounded to the nearest foot) of the true dimensions or within 5 percent of the area. (One foot equates to approximately

30 centimeters in the metric system.) If areas, dimensions, or volumes must be estimated, the property record should

note the instances in which quantities are estimated.

• For each objective, categorical, or binary data field to be collected or verified, at least 95 percent of the coded entries

should be accurate. Objective, categorical, or binary data characteristics include such attributes as exterior wall

material, number of full bathrooms, and waterfront view. As an example, if a data collector captures 10 objective,

categorical, or binary data items for 100 properties, at least 950 of the 1,000 total entries should be correct.

• For each subjective categorical data field collected or verified, data should be coded correctly at least 90 percent of

the time. Subjective categorical data characteristics include data items such as quality grade, physical condition, and

architectural style.

STANDARD ON MASS APPRAISAL OF REAL PROPERTY—2017

4

• Regardless of specific accuracy requirements, consistent measurement is important. Standards including national, local

and regional practices exist to support consistent measurement. The standard of measurement should be documented

as part of the process. (American Institute of Architects 1995; Marshall & Swift Valuation Service 2017; International

Property Measurement Standards Coalition n.d.; Building Owners and Managers Association International 2017)

3.3.2.5 Data Collection Quality Control

A quality control program is necessary to ensure that data accuracy standards are achieved and maintained. Indepen-

dent quality control inspections should occur immediately after the data collection phase begins and may be performed

by jurisdiction staff, project consultants, auditing firms, or oversight agencies. The inspections should review random

samples of finished work for completeness and accuracy and keep tabulations of items coded correctly or incorrectly, so

that statistical tests can be used to determine whether accuracy standards have been achieved. Stratification by geographic

area, property type, or individual data collector can help detect patterns of data error. Data that fail to meet quality control

standards should be recollected.

The accuracy of subjective data should be judged primarily by conformity with written specifications and examples in

the data collection manual. The data reviewer should substantiate subjective data corrections with pictures or field notes.

3.3.3 Data Entry

To avoid duplication of effort, the data collection form should be able to serve as the data entry form. Data entry should

be routinely audited to ensure accuracy.

Data entry accuracy should be as close to 100 percent as possible and should be supported by a full set of range and

consistency edits. These are error or warning messages generated in response to invalid or unusual data items. Examples

of data errors include missing data codes and invalid characters. Warning messages should also be generated when data

values exceed normal ranges (e.g., more than eight rooms in a 1,200-square-foot residence). The warnings should appear

as the data are entered. When feasible, action on the warnings should take place during data entry. Field data entry devices

provide the ability to edit data as it is entered and also eliminate data transcription errors.

3.3.4 Maintaining Property Characteristics Data

Property characteristics data should be continually updated in response to changes brought about by new construction,

new parcels, remodeling, demolition, and destruction. There are several ways of updating data. The most efficient method

involves building permits. Ideally, strictly enforced local ordinances require building permits for all significant construc-

tion activity, and the assessor's office receives copies of the permits. This method allows the assessor to identify properties

whose characteristics are likely to change, to inspect such parcels on a timely basis (preferably as close to the assessment

date as possible), and to update the files accordingly.

Another method is aerial photography, which also can be helpful in identifying new or previously unrecorded construc-

tion and land use.

Some jurisdictions use self-reporting, in which property owners review the assessor’s records and submit additions or

corrections. Information derived from multiple listing sources and other third-party vendors can also be used to validate

property records.

Periodic field inspections can help ensure that property characteristics data are complete and accurate. Assuming that most

new construction activity is identified through building permits or other ongoing procedures, a physical review including

an on-site verification of property characteristics should be conducted at least every 4 to 6 years. Reinspections should

include partial remeasurement of the two most complex sides of improvements and a walk around the improvement to

identify additions and deletions. Photographs taken at previous physical inspections can help identify changes.

5

STANDARD ON MASS APPRAISAL OF REAL PROPERTY—2017

3.3.5 Alternative to Periodic On-site Inspections

Provided that initial physical inspections are timely completed and that an effective system of building permits or other

methods of routinely identifying physical changes is in place, jurisdictions may employ a set of digital imaging technol-

ogy tools to supplement field reinspections with a computer-assisted office review. These imaging tools should include

the following:

• Current high-resolution street-view images (at a sub-inch pixel resolution that enables quality grade and physical

condition to be verified)

• Orthophoto images (minimum 6-inch pixel resolution in urban/suburban and 12-inch resolution in rural areas,

updated every 2 years in rapid-growth areas or 6–10 years in slow-growth areas)

• Low-level oblique images capable of being used for measurement verification (four cardinal directions, minimum

6-inch pixel resolution in urban/suburban and 12-inch pixel resolution in rural areas, updated every 2 years in rapid-

growth areas or 6–10 years in slow-growth areas).

These tool sets may incorporate change detection techniques that compare building dimension data (footprints) in the

CAMA system to georeferenced imagery or remote sensing data from sources (such as LiDAR [light detection and rang-

ing]) and identify potential CAMA sketch discrepancies for further investigation.

Assessment jurisdictions and oversight agencies must ensure that images meet expected quality standards. Standards

required for vendor-supplied images should be spelled out in the Request for Proposal (RFP) and contract for services,

and images should be checked for compliance with specified requirements. For general guidance on preparing RFPs and

contracting for vendor-supplied services, see the Standard on Contracting for Assessment Services [IAAO 2008].

In addition, appraisers should visit assigned areas on an annual basis to observe changes in neighborhood condition, trends,

and property characteristics. An on-site physical review is recommended when significant construction changes are de-

tected, a property is sold, or an area is affected by catastrophic damage. Building permits should be regularly monitored

and properties that have significant change should be inspected when work is complete.

3.4 Sale Data

States and provinces should seek mandatory disclosure laws to ensure comprehensiveness of sale data files. Regardless

of the availability of such statutes, a file of sale data must be maintained, and sales must be properly reviewed and vali-

dated. Sale data are required in all applications of the sales comparison approach, in the development of land values and

market-based depreciation schedules in the cost approach, and in the derivation of capitalization rates or discount rates in

the income approach. Refer to Mass Appraisal of Real Property (Gloudemans 1999, chapter 2) or Fundamentals of Mass

Appraisal (Gloudemans and Almy 2011 chapter 2) for guidelines on the acquisition and processing of sale data.

3.5 Income and Expense Data

Income and expense data must be collected for income-producing property and reviewed by qualified appraisers to ensure

their accuracy and usability for valuation analysis (see Section 4.4.). Refer to Mass Appraisal of Real Property (Gloudemans

1999, chapter 2) or Fundamentals of Mass Appraisal (Gloudemans and Almy 2011, chapter 2) for guidelines addressing

the collection and processing of income and expense data.

3.6 Cost and Depreciation Data

Current cost and depreciation data adjusted to the local market are required for the cost approach (see Section 4.2). Cost

and depreciation manuals and schedules can be purchased from commercial services or created in-house. See Mass Ap-

praisal of Real Property (Gloudemans 1999, chapter 4) or Fundamentals of Mass Appraisal (Gloudemans and Almy 2011,

180–193) for guidelines on creating manuals and schedules.

STANDARD ON MASS APPRAISAL OF REAL PROPERTY—2019

6

4. Valuation

Mass appraisal analysis begins with assigning properties to use classes or strata based on highest and best use, which

normally equates to current use. Some statutes require that property be valued for ad valorem tax purposes at current use

regardless of highest and best use. Zoning and other land use controls normally dictate highest and best use of vacant

land. In the absence of such restrictions, the assessor must determine the highest and best use of the land by analyzing the

four components—legally permissible, physically possible, appropriately supported, and financially feasible—thereby

resulting in the highest value. Special attention may be required for properties in transition, interim or nonconforming

uses, multiple uses, and excess land.

4.1 Valuation Models

Any appraisal, whether single-property appraisal or mass appraisal, uses a model, that is, a representation in words or an

equation of the relationship between value and variables representing factors of supply and demand. Mass appraisal models

attempt to represent the market for a specific type of property in a specified area. Mass appraisers must first specify the

model, that is, identify the supply and demand factors and property features that influence value, for example, square feet

of living area. Then they must calibrate the model, that is, determine the adjustments or coefficients that best represent the

value contribution of the variables chosen, for example, the dollar amount the market places on each square foot of living

area. Careful and extensive market analysis is required for both specification and calibration of a model that estimates

values accurately. Mass appraisal models apply to all three approaches to value: the cost approach, the sales comparison

approach, and the income approach.

Valuation models are developed for defined property groups. For residential properties, geographic stratification is ap-

propriate when the value of property attributes varies significantly among areas and each area is large enough to provide

adequate sales. It is particularly effective when housing types and styles are relatively uniform within areas. Separate

models are developed for each market area (also known as economic or model areas). Subareas or neighborhoods can

serve as variables in the models and can also be used in land value tables and selection of comparable sales. (See Mass Ap-

praisal of Real Property [Gloudemans 1999, 118–120] or Fundamentals of Mass Appraisal [Gloudemans and Almy 2011,

139–143] for guidelines on stratification.) Smaller jurisdictions may find it sufficient to develop a single residential model.

Commercial and income-producing properties should be stratified by property type. In general, separate models should

be developed for apartment, warehouse/industrial, office, and retail properties. Large jurisdictions may be able to stratify

apartment properties further by type or area or to develop multiple models for other income properties with adequate data.

4.2 The Cost Approach

The cost approach is applicable to virtually all improved parcels and, if used properly, can produce accurate valuations.

The cost approach is more reliable for newer structures of standard materials, design, and workmanship. It produces an

estimate of the value of the fee simple interest in a property.

Reliable cost data are imperative in any successful application of the cost approach. The data must be complete, typical,

and current. Current construction costs should be based on the cost of replacing a structure with one of equal utility, us-

ing current materials, design, and building standards. In addition to specific property types, cost models should include

the cost of individual construction components and building items in order to adjust for features that differ from base

specifications. These costs should be incorporated into a construction cost manual and related computer software. The

software can perform the valuation function, and the manual, in addition to providing documentation, can be used when

nonautomated calculations are required.

Construction cost schedules can be developed in-house, based on a systematic study of local construction costs, obtained

from firms specializing in such information, or custom-generated by a contractor. Cost schedules should be verified for

accuracy by applying them to recently constructed improvements of known cost. Construction costs also should be up-

dated before each assessment cycle.

7

STANDARD ON MASS APPRAISAL OF REAL PROPERTY—2019

The most difficult aspects of the cost approach are estimates of land value and accrued depreciation. These estimates

must be based on non-cost data (primarily sales) and can involve considerable subjectivity. Land values used in the cost

approach must be current and consistent. Often, they must be extracted from sales of improved property because sales of

vacant land are scarce. Section 4.5 provides standards for land valuation in mass appraisal.

Depreciation schedules can be extracted from sales data in several ways. See Mass Appraisal of Real Property (Gloude-

mans 1999, chapter 4) or Fundamentals of Mass Appraisal (Gloudemans and Almy 2011, 189–192).

4.3 The Sales Comparison Approach

The sales comparison approach estimates the value of a subject property by statistically analyzing the sale prices of similar

properties. This approach is usually the preferred approach for estimating values for residential and other property types

with adequate sales.

Applications of the sales comparison approach include direct market models and comparable sales algorithms (see Mass

Appraisal of Real Property [Gloudemans 1999, chapters 3 and 4], Fundamentals of Mass Appraisal [Gloudemans and

Almy 2011, chapters 4 and 6], and the Standard on Automated Valuation Models (AVMs) [IAAO 2018]). Comparable

sales algorithms are most akin to single-property appraisal applications of the sales comparison approach. They have the

advantages of being familiar and easily explained and can compensate for less well-specified or calibrated models, be-

cause the models are used only to make adjustments to the selected comparables. They can be problematic if the selected

comparables are not well validated or representative of market value. Because they predict market value directly, direct

market models depend more heavily on careful model specification and calibration. Their advantages include efficiency

and consistency, because the same model is directly applied against all properties in the model area.

Users of comparable sales algorithms should be aware that sales ratio statistics will be biased if sales used in the ratio

study are used as comparables for themselves in model development. This problem can be avoided by (1) not using sales

as comparables for themselves in modeling or (2) using holdout or later sales in ratio studies.

4.4 The Income Approach

In general, for income-producing properties, the income approach is the preferred valuation approach when reliable income

and expense data are available, along with well-supported income multipliers, overall rates, and required rates of return

on investment. Successful application of the income approach requires the collection, maintenance, and careful analysis

of income and expense data.

Mass appraisal applications of the income approach begin with collecting and processing income and expense data. (These

data should be expressed on an appropriate per-unit basis, such as per square foot or per apartment unit.) Appraisers should

then compute normal or typical gross incomes, vacancy rates, net incomes, and expense ratios for various homogeneous

strata of properties. These figures can be used to judge the reasonableness of reported data for individual parcels and to

estimate income and expense figures for parcels with unreported data. Actual or reported figures can be used as long as

they reflect typical figures (or typical figures can be used for all properties).

Alternatively, models for estimating gross or net income and expense ratios can be developed by using actual income

and expense data from a sample of properties and calibrated by using multiple regression analysis. For an introduction to

income modeling, see Mass Appraisal of Real Property (Gloudemans 1999, chapter 3) or Fundamentals of Mass Appraisal

(Gloudemans and Almy 2011, chapter 9). The developed income figures can be capitalized into estimates of value in a

number of ways. The most direct method involves the application of gross income multipliers, which express the ratio of

market value to gross income. At a more refined level, net income multipliers or their reciprocals, overall capitalization

rates, can be developed and applied. Provided there are adequate sales, these multipliers and rates should be extracted

from a comparison of actual or estimated incomes with sale prices (older income and sales data should be adjusted to the

valuation date as appropriate). Income multipliers and overall rates developed in this manner tend to provide reliable,

consistent, and readily supported valuations when good sales and income data are available. When adequate sales are not

available, relevant publications and local market participants can be consulted.

STANDARD ON MASS APPRAISAL OF REAL PROPERTY—2017

8

4.5 Land Valuation

State or local laws may require the value of an improved parcel to be separated into land and improvement components.

When the sales comparison or income approach is used, an independent estimate of land value can be made and subtracted

from the total property value to obtain a residual improvement value. Some computerized valuation techniques provide a

separation of total value into land and building components.

Land values should be reviewed annually. At least once every 4 to 6 years the properties should be physically inspected and

revalued. The sales comparison approach is the primary approach to land valuation and is always preferred when sufficient

sales are available. In the absence of adequate sales, other techniques that can be used in land appraisal include allocation,

abstraction, anticipated use, capitalization of ground rents, and land residual capitalization. (See Mass Appraisal of Real

Property [Gloudemans 1999, chapter 3] or Fundamentals of Mass Appraisal [Gloudemans and Almy 2011, 178–180].)

4.6 Considerations by Property Type

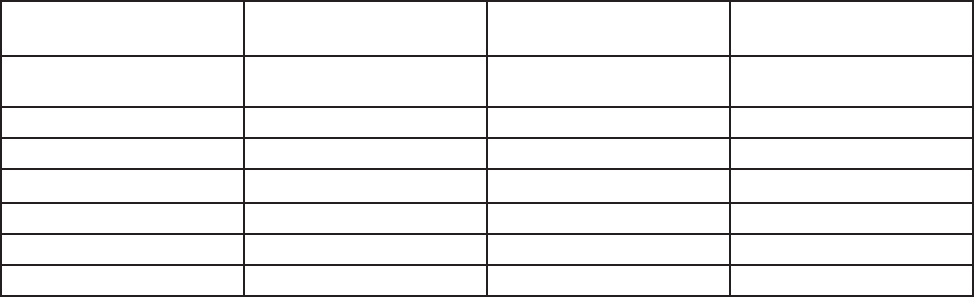

The appropriateness of each valuation approach varies with the type of property under consideration. Table 1 ranks the

relative usefulness of the three approaches in the mass appraisal of major types of properties. The table assumes that there

are no major statutory barriers to using all three approaches or to obtaining cost, sales, and income data. Although relying

only on the single best approach for a given type of property can have advantages in terms of efficiency and consistency,

the use of two or more approaches provides helpful cross-checks and flexibility and can thus produce greater accuracy,

particularly for less typical properties.

Table 1. Rank of typical usefulness of the three approaches to value in the mass appraisal of major types of property

Type of Property Cost Approach Sales Comparison

Approach

Income Approach

Single-family

residential

2 1 3

Multifamily residential 3 1,2 1,2

Commercial 3 2 1

Industrial 1,2 3 1,2

Nonagricultural land - 1 2

Agricultural

a

- 2 1

Special-purpose

b

1 2,3 2,3

a

Includes farm, ranch, and forest properties.

b

Includes institutional, governmental, and recreation properties.

4.6.1 Single-Family Residential Property

The sales comparison approach is the best approach for single-family residential property, including condominiums.

Automated versions of this approach are highly efficient and generally accurate for the majority of these properties. The

cost approach is a good supplemental approach and should serve as the primary approach when the sales data available

are inadequate. The income approach is usually inappropriate for mass appraisal of single-family residential properties,

because most of these properties are not rented.

4.6.2 Manufactured Housing

Manufactured or mobile homes can be valued in a number of ways depending on the local market and ownership status.

Often mobile homes are purchased separately and situated on a rented space in a mobile home park. In this case the best

strategy is to model the mobile homes separately from the land. At other times mobile homes are situated on individual

lots and bought and sold similar to stick-built homes. Particularly in rural areas they may be intermixed with stick-built

homes. In these cases, they can be modeled in a manner similar to that for other residential properties and included in the

same models, as long as the model includes variables to distinguish them and recognize any relevant differences from

other homes (e.g., mobile homes may appreciate at a rate different from that for stick-built homes).

9

STANDARD ON MASS APPRAISAL OF REAL PROPERTY—2017

4.6.3 Multifamily Residential Property

The sales comparison and income approaches are preferred in valuing multifamily residential property when sufficient

sales and income data are available. Multiple regression analysis (MRA) and related techniques have been successfully

used in valuing this property type. Where adequate sales are available, direct sales models can be used. MRA also can

be used to calibrate different portions of the income approach, including the estimation of market rents and development

of income multipliers or capitalization rates. As with other residential property, the cost approach is useful in providing

supplemental valuations and can serve as the primary approach when good sales and income data are not available.

4.6.4 Commercial and Industrial Property

The income approach is the most appropriate method in valuing commercial and industrial property if sufficient income

data are available. Direct sales comparison models can be equally effective in large jurisdictions with sufficient sales.

When a sufficient supply of sales data and income data is not available, the cost approach should be applied. However,

values generated should be checked against available sales data. Cost factors, land values, and depreciation schedules

must be kept current through periodic review.

4.6.5 Nonagricultural Land

The sales comparison approach is preferred for valuing nonagricultural land. Application of the sales comparison approach

to vacant land involves the collection of sales data, the posting of sales data on maps, the calculation of standard unit

values (such as value per square foot, per front foot, or per parcel) by area and type of land use, and the development of

land valuation maps or computer-generated tables in which the pattern of values is displayed. When vacant land sales are

not available or are few, additional benchmarks can be obtained by subtracting the replacement cost new less depreciation

of improvements from the sale prices of improved parcels. The success of this technique requires reliable cost data and

tends to work best for relatively new improvements, for which depreciation is minimal.

Another approach is a hybrid model decomposable into land and building values. Although these models can be cali-

brated from improved sales alone, separation of value between land and buildings is more reliable when both vacant and

improved sales are available.

4.6.6 Agricultural Property

If adequate sales data are available and agricultural property is to be appraised at market value, the sales comparison

approach is preferred. However, most states and provinces provide for the valuation of agricultural land at use value,

making the sales comparison approach inappropriate for land for which market value exceeds use value. Thus, it is often

imperative to obtain good income data and to use the income approach for agricultural land. Land rents are often avail-

able, sometimes permitting the development and application of overall capitalization rates. Many states and provinces

have soil maps that assign land to different productivity classes for which typical rents can be developed. Cost tables can

be used to value agricultural buildings.

4.6.7 Special-Purpose Property

The cost approach tends to be most appropriate in the appraisal of special-purpose properties, because of the distinctive

nature of such properties and the general absence of adequate sales or income data.

4.7 Value Reconciliation

When more than one approach or model is used for a given property group, the appraiser must determine which to use or

emphasize. Often this can be done by comparing ratio study statistics. Although there are advantages to being consistent,

sometimes an alternative approach or method is more reliable for special situations and atypical properties. CAMA systems

should allow users to document the approach or method being used for each property.

4.8 Frequency of Reappraisals

Section 4.2.2 of the Standard on Property Tax Policy (IAAO 2010) states that current market value implies annual as-

sessment of all property. Annual assessment does not necessarily mean, however, that each property must be re-examined

each year. Instead, models can be recalibrated, or market adjustment factors derived from ratio studies or other market

analyses applied based on criteria such as property type, location, size, and age.

STANDARD ON MASS APPRAISAL OF REAL PROPERTY—2017

10

Analysis of ratio study data can suggest groups or strata of properties in greatest need of physical review. In general, market

adjustments can be highly effective in maintaining equity when appraisals are uniform within strata and recalibration can

provide even greater accuracy. However, only physical reviews can correct data errors and, as stated in Sections 3.3.4 and

3.3.5, property characteristics data should be reviewed and updated at least every 4 to 6 years. This can be accomplished

in at least three ways:

• Reinspecting all property at periodic intervals (i.e., every 4 to 6 years)

• Reinspecting properties on a cyclical basis (e.g., one-fourth or one-sixth each year)

• Reinspecting properties on a priority basis as indicated by ratio studies or other considerations while still ensuring

that all properties are examined at least every sixth year

5. Model Testing, Quality Assurance, and Value Defense

Mass appraisal allows for model testing and quality assurance measures that provide feedback on the reliability of valua-

tion models and the overall accuracy of estimated values. Modelers and assessors must be familiar with these diagnostics

so they can evaluate valuation performance properly and make improvements where needed.

5.1 Model Diagnostics

Modeling software contains various statistical measures that provide feedback on model performance and accuracy. MRA

software contains multiple sets of diagnostic tools, some of which relate to the overall predictive accuracy of the model

and some of which relate to the relative importance and statistical reliability of individual variables in the model. Modelers

must understand these measures and ensure that final models not only make appraisal sense but also are statistically sound.

5.2 Sales Ratio Analyses

Regardless of how values were generated, sales ratio studies provide objective, bottom-line indicators of assessment per-

formance. The IAAO literature contains extensive discussions of this important topic, and the Standard on Ratio Studies

(2013) provides guidance for conducting a proper study. It also presents standards for key ratio statistics relating to the two

primary aspects of assessment performance: level and uniformity. The following discussion summarizes these standards

and describes how the assessor can use sales ratio metrics to help ensure accurate, uniform values.

5.2.1 Assessment Level

Assessment level relates to the overall or general level of assessment of a jurisdiction and various property classes, strata,

and groups within the jurisdiction. Each group must be assessed at market value as required by professional standards and

applicable statutes, rules, and related requirements. The three common measures of central tendency in ratio studies are

the median, mean, and weighted mean. The Standard on Ratio Studies (2013) stipulates that the median ratio should be

between 0.90 and 1.10 and provides criteria for determining whether it can be concluded that the standard has not been

achieved for a property group. Current, up-to-date valuation models, schedules, and tables help ensure that assessment

levels meet required standards, and values can be statistically adjusted between full reappraisals or model recalibrations

to ensure compliance.

5.2.2 Assessment Uniformity

Assessment uniformity relates to the consistency and equity of values. Uniformity has several aspects, the first of which

relates to consistency in assessment levels between property groups. It is important to ensure, for example, that residential

and commercial properties are appraised at similar percentages of market value (regardless of the legal assessment ratios

that may then be applied) and that residential assessment levels are consistent among neighborhoods, construction classes,

age groups, and size groups. Consistency among property groups can be evaluated by comparing measures of central

tendency calculated for each group.

Various graphs can also be used for this purpose. The Standard on Ratio Studies (IAAO 2013) stipulates that the level of

appraisal for each major group of properties should be within 5 percent of the overall level for the jurisdiction and provides

criteria for determining whether it can be concluded from ratio data that the standard has not been met.

11

STANDARD ON MASS APPRAISAL OF REAL PROPERTY—2017

Another aspect of uniformity relates to the consistency of assessment levels within property groups. There are several

such measures, the preeminent of which is the coefficient of dispersion (COD), which represents the average percentage

deviation from the median ratio. The lower the COD, the more uniform the ratios within the property group. In addition,

uniformity can be viewed spatially by plotting sales ratios on thematic maps.

The Standard on Ratio Studies (IAAO 2013) provides the following standards for the COD:

• Single-family homes and condominiums: CODs of 5 to 10 for newer or fairly similar residences and 5 to 15 for

older or more heterogeneous areas

• Income-producing properties: CODs of 5 to 15 in larger, urban areas and 5 to 20 in other areas

• Vacant land: CODs of 5 to 20 in urban areas and 5 to 25 in rural or seasonal recreation areas

• Rural residential, seasonal, and manufactured homes: CODs of 5 to 20.

The entire appraisal staff must be aware of and monitor compliance with these standards and take corrective action where

necessary. Poor uniformity within a property group is usually indicative of data problems or deficient valuation procedures

or tables and cannot be corrected by application of market adjustment factors.

A final aspect of assessment uniformity relates to equity between low- and high-value properties. Although there are sta-

tistical subtleties that can bias evaluation of price-related uniformity, the IAAO literature (see particularly Fundamentals

of Mass Appraisal [Gloudemans and Almy 2011, 385–392 and Appendix B] and the Standard on Ratio Studies [IAAO

2013]) provides guidance and relevant measures, namely, the price-related differential (PRD) and coefficient of price-

related bias (PRB).

The PRD provides a simple gauge of price-related bias. The Standard on Ratio Studies (IAAO 2013) calls for PRDs of

0.98 to 1.03. PRDs below 0.98 tend to indicate assessment progressivity, the condition in which assessment ratios increase

with price. PRDs above 1.03 tend to indicate assessment regressivity, in which assessment ratios decline with price. The

PRB indicates the percentage by which assessment ratios change whenever values double or are halved. For example, a

PRB of −0.03 would mean that assessment levels fall by 3 percent when value doubles. The Standard on Ratio Studies

calls for PRBs of −0.05 to +0.05 and regards PRBs outside the range of −0.10 to +0.10 as unacceptable.

Because price is observable only for sale properties, there is no easy correction for the PRB, which is usually due to

problems in valuation models and schedules. Sometimes other ratio study diagnostics will provide clues. For example,

high ratios for lower construction classes may indicate that base rates should be reduced for those classes, which should

in turn improve assessment ratios for low-value properties.

5.3 Holdout Samples

Holdout samples are validated sales that are not used in valuation but instead are used to test valuation performance. Holdout

samples should be randomly selected with a view to obtaining an adequate sample while ensuring that the number of sales

available for valuation will provide reliable results for the range of properties that must be valued (holdout samples of 10

to 20 percent are typical). If too few sales are available, later sales can be validated and used for the same purpose. (For

a method of using sales both to develop and test valuation models, see "The Use of Cross-validation in CAMA Modeling

to Get the Most Out of Sales" (Jensen 2011).

Since they were not used in valuation, holdout samples can provide more objective measures of valuation performance. This

can be particularly important when values are not based on a common algorithm as cost and MRA models are. Manually

assigning land values, for example, might produce sales ratio statistics that appear excellent but are not representative of

broader performance for both sold and unsold properties. Comparable sales models that value a sold property using the

sale of a property as a comparable for itself can produce quite different results when tested on a holdout group.

When a new valuation approach or technique is used for the first time, holdout sales can be helpful in validating use of

the new method. In general, however, holdout samples are unnecessary as long as valuation models are based on common

algorithms and schedules and the value assigned to a sale property is not a function of its price. Properly validated later

sales can provide follow-up performance indicators without compromising the number of sales available for valuation.

STANDARD ON MASS APPRAISAL OF REAL PROPERTY—2017

12

5.4 Documentation

Valuation procedures and models should be documented. Appraisal staff should have at least a general understanding of

how the models work and the various rates and adjustments made by the models. Cost manuals should be current and

contain the rates and adjustments used to value improvements by the cost approach. Similarly, land values should be

supported by tables of rates and adjustments for features such as water frontage, traffic, and other relevant influences.

MRA models and other sales comparison algorithms should document final equations and should be reproducible, so that

rerunning the model produces the same value. Schedules of rental rates, vacancy rates, expense ratios, income multipliers,

and capitalization rates should document how values based on the income approach were derived.

It can be particularly helpful to prepare a manual, booklet, or report for each major property type that provides a narrative

summary of the valuation approach and methodology and contains at least the more common rates and adjustments. Ex-

amples of how values were computed for sample properties can be particularly helpful. The manuals serve as a resource

for current staff and can be helpful in training new staff or explaining the valuation process to other interested parties.

Once prepared, the documents should be updated when valuation schedules change or methods and calculation procedures

are revised.

5.5 Value Defense

The assessment office staff must have confidence in the appraisals and be able to explain and defend them. This confi-

dence begins with application of reliable appraisal techniques, generation of appropriate valuation reports, and review

of preliminary values. It may be helpful to have reports that list each parcel, its characteristics, and its calculated value.

Parcels with unusual characteristics, extreme values, or extreme changes in values should be identified for subsequent

individual review. Equally important, summary reports should show average values, value changes, and ratio study sta-

tistics for various strata of properties. These should be reviewed to ensure the overall consistency of values for various

types of property and various locations. (See the Uniform Standards of Professional Appraisal Practice, Standards Rule

6-7, for reporting requirements for mass appraisals [The Appraisal Foundation 2012–2013].)

The staff should also be prepared to support individual valuations as required, preferably through comparable sales. At

a minimum, staff should be able to produce a property record and explain the basic approach (cost, sales comparison, or

income) used to estimate the value of the property. A property owner should never be told simply that “the computer” or

“the system” produced the appraisal. In general, the staff should tailor the explanation to the taxpayer’s knowledge and

expertise. Equations converted to tabular form can be used to explain the basis for valuation. In all cases, the assessment

office staff should be able to produce sales or appraisals of similar properties in order to support (or at least explain) the

valuation of the property in question. Comparable sales can be obtained from reports that list sales by such features as

type of property, area, size, and age. Alternatively, interactive programs can be obtained or developed that identify and

display the most comparable properties.

Assessors should notify property owners of their valuations in sufficient time for property owners to discuss their apprais-

als with the assessor and appeal the value if they choose to do so (see the Standard on Public Relations [IAAO 2011]).

Statutes should provide for a formal appeals process beyond the assessor’s level (see the Standard on Assessment Appeal

[IAAO 2016a]).

6. Managerial and Space Considerations

6.1 Overview

Mass appraisal requires staff, technical, and other resources. This section discusses certain key managerial and facilities

considerations.

6.2 Staffing and Space

A successful in-house appraisal program requires trained staff and adequate facilities in which to work and meet with the

public.

13

STANDARD ON MASS APPRAISAL OF REAL PROPERTY—2017

6.2.1 Staffing

Staff should comprise persons skilled in general administration, supervision, appraisal, mapping, data processing, and

clerical functions. Typical staffing sizes and patterns for jurisdictions of various sizes are illustrated in Fundamentals

of Mass Appraisal (Gloudemans and Almy 2011, 22–25). Staffing needs can vary significantly based on factors such as

frequency of reassessments.

6.2.2 Space Considerations

The following minimum space standards are suggested for managerial, supervisory, and support staff:

• Chief assessing officer (e.g., Assessor, director)—a private office, enclosed by walls or windows extending to the

ceiling, of 200 square feet (18 to 19 square meters)

• Management position (e.g., chief deputy assessor, head of a division in a large jurisdiction, and so on)—a private

office, enclosed by walls or windows extending to the ceiling, of 170 square feet (15 to 16 square meters)

• Supervisory position (head of a section, unit, or team of appraisers, mappers, analysts, technicians, or clerks)—a

private office or partitioned space of 150 square feet (14 square meters)

• Appraisers and technical staff—private offices or at least partitioned, quiet work areas of 50 to 100 square feet

(5 to 10 square meters), not including aisle and file space, with a desk and chair

• Support staff—adequate workspace, open or partitioned, to promote intended work functions and access.

In addition, there should be adequate space for

• File storage and access

• Training and meetings

• Mapping and drafting

• Public service areas

• Printing and photocopy equipment

• Library facilities.

6.3 Data Processing Support

CAMAs require considerable data processing support.

6.3.1 Hardware

The hardware should be powerful enough to support applications of the cost, sales comparison, and income approaches,

as well as data maintenance and other routine operations. Data downloading, mass calculations, GIS applications, and

Web support tend to be the most computer-intensive operations. Processing speed and efficiency requirements should

be established before hardware acquisition. Computer equipment can be purchased, leased, rented, or shared with other

jurisdictions. If the purchase option is chosen, the equipment should be easy to upgrade to take advantage of technological

developments without purchasing an entirely new system.

6.3.2 Software

CAMA software can be developed internally, adapted from software developed by other public agencies, or purchased

(in whole or in part) from private vendors. (Inevitably there will be some tailoring needed to adapt externally developed

software to the requirements of the user’s environment.) Each alternative has advantages and disadvantages. The software

should be designed so that it can be easily modified; it should also be well documented, at both the appraiser/user and

programmer levels.

CAMA software works in conjunction with various general-purpose software, typically including word processing,

spreadsheet, statistical, and GIS programs. These programs and applications must be able to share data and work together

cohesively.

STANDARD ON MASS APPRAISAL OF REAL PROPERTY—2017

14

Security measures should exist to prevent unauthorized use and to provide backup in the event of accidental loss or de-

struction of data.

6.3.2.1 Custom Software

Custom software is designed to perform specific tasks, identified by the jurisdiction, and can be specifically tailored to the

user’s requirements. The data screens and processing logic can often be customized to reflect actual or desired practices,

and the prompts and help information can be tailored to reflect local terminology and convention.

After completing the purchase or license requirements, the jurisdiction should retain access to the program source code,

so other programmers are able to modify the program to reflect changing requirements.

The major disadvantages of custom software are the time and expense of writing, testing, and updating. Particular attention

must be paid to ensuring that user requirements are clearly conveyed to programmers and reflected in the end product,

which should not be accepted until proper testing has been completed. Future modifications to programs, even those of

a minor nature, can involve system administrator approval and can be a time-consuming, costly, and rigorous job. (See

Standard on Contracting for Assessment Services [IAAO 2019].)

6.3.2.2 Generic Software

An alternative to custom software is generic software, of which there are two major types: vertical software, which is written

for a specific industry, and horizontal software, which is written for particular applications regardless of industry. Examples

of the latter include database, spreadsheet, word processing, and statistical software. Although the actual instruction code

within these programs cannot be modified, they typically permit the user to create a variety of customized templates, files,

and documents that can be processed. These are often referred to as commercial off-the-shelf software (COTS) packages.

Generic vertical software usually requires modification to fit a jurisdiction’s specific needs. In considering generic soft-

ware, the assessor should determine

• System requirements

• The extent to which the software meets the agency’s needs

• A timetable for implementation

• How modifications will be accomplished

• The level of vendor support

• Whether the source code can be obtained.

(See Standard on Contracting for Assessment Services [IAAO 2019].)

Horizontal generic software is more flexible, permitting the user to define file structures, relational table layout, input and

output procedures, including form or format, and reports. Assessment offices with expertise in such software (which does

not imply a knowledge of programming) can adapt it for

• Property (data) file maintenance

• Market research and analysis

• Valuation modeling and processing

• Many other aspects of assessment operations.

Horizontal generic software is inexpensive and flexible. However, it requires considerable customization to adapt it to

local requirements. Provisions should be made for a sustainable process that is not overly dependent on a single person

or resource.

15

STANDARD ON MASS APPRAISAL OF REAL PROPERTY—2017

6.4 Contracting for Appraisal Services

Reappraisal contracts can include mapping, data collection, data processing, and other services, as well as valuation. They

offer the potential of acquiring professional skills and resources quickly. These skills and resources often are not available

internally. Contracting for these services not only can allow the jurisdiction to maintain a modest staff and to budget for

reappraisal on a periodic basis, but also makes the assessor less likely to develop in-house expertise. (See the Standard

on Contracting for Assessment Services [IAAO 2019].)

6.5 Benefit-Cost Considerations

6.5.1 Overview

The object of mass appraisal is to produce equitable valuations at low costs. Improvements in equity often require in-

creased expenditures.

Benefit-cost analysis in mass appraisal involves two major issues: policy and administration.

6.5.2 Policy Issues

An assessment jurisdiction requires a certain expenditure level simply to inventory, list, and value properties. Beyond

that point, additional expenditures make possible rapid improvements in equity initially, but marginal improvements in

equity diminish as expenditures increase. At a minimum, jurisdictions should budget to meet statutory requirements and

the performance standards contained in the Standard on Ratio Studies (IAAO 2013) and summarized in Section 5.2.

6.5.3 Administrative Issues

Maximizing equity per dollar of expenditure is the primary responsibility of assessment administration. To maximize

productivity, the assessor and managerial staff must effectively plan, budget, organize, and control operations and provide

leadership. This must be accomplished within the office’s legal, fiscal, economic, and social environment and constraints

(Eckert, Gloudemans, and Kenyon 1990, chapter 16).

7. Reference Materials

Reference materials are needed in an assessment office to promote compliance with laws and regulations, uniformity in

operations and procedures, and adherence to generally accepted assessment principles and practices.

7.1 Standards of Practice

The standards of practice may incorporate or be contained in laws, regulations, policy memoranda, procedural manuals,

appraisal manuals and schedules, standard treatises on property appraisal and taxation (see section 6.2). Written standards

of practice should address areas such as personal conduct, collection of property data, coding of information for data

processing. The amount of detail will vary with the nature of the operation and the size of the office.

7.2 Professional Library

Every assessment office should have access to a comprehensive professional library that contains the information staff

needs. A resource library may be digital or physical and should include the following:

• Property tax laws and regulations

• IAAO standards

• Historical resources

• Current periodicals

• Manuals and schedules

• Equipment manuals and software documentation.

STANDARD ON MASS APPRAISAL OF REAL PROPERTY—2017

16

References

American Institute of Architects. 1995. D101–1995, Methods of Calculating Areas and Volumes of Buildings. Washington,

D.C.: The American Institute of Architects.

Building Owners and Managers Association International. 2017. “BOMA Standards.” http://boma.org/standards/Pages/

default.aspx (accessed February 20, 2017).

Eckert, J., R. Gloudemans, and R. Almy, ed. 1990. Property Appraisal and Assessment Administration. Chicago: IAAO.

Gloudemans, R.J. 1999. Mass Appraisal of Real Property. Chicago: International Association of Assessing Officers (IAAO).

Gloudemans, R.J., and R.R. Almy. 2011. Fundamentals of Mass Appraisal. Kansas City: IAAO.

IAAO. 2018. Standard on Automated Valuation Models (AVMs). Chicago: IAAO.

____. 2019. Standard on Contracting for Assessment Services. Kansas City: IAAO.

____. 2010. Standard on Property Tax Policy. Kansas City: IAAO.

____. 2011. Standard on Public Relations. Kansas City: IAAO.

____. 2013. Standard on Ratio Studies. Kansas City: IAAO.

____. 2015. Standard on Digital Cadastral Maps and Parcel Identifiers. Kansas City: IAAO.

____. 2016a. Standard on Assessment Appeal. Kansas City: IAAO.

____. 2016b. Standard on Manual Cadastral Maps and Parcel Identifiers. Kansas City: IAAO.

International Property Measurement Standards Coalition. (n.d.) IPMSC Standards. https://ipmsc.org/standards/ (accessed

February 20, 2017).

Jensen, D.L. 2011. “The Use of Cross-Validation in CAMA Modeling to Get the Most out of Sales.” Journal of Property

Tax & Assessment Administration 8 (3): 19–40.

Marshall & Swift Valuation Service. 2017. “A Complete Guide to Commercial Building Costs.” http://www.corelogic.

com/products/marshall-swift-valuation-service.aspx (accessed October 15, 2017).

National Research Council. 1983. Procedures and Standards for a Multipurpose Cadastre. Washington, DC: National

Research Council.

R.S. Means. 2017. “R.S. Means Standards.” https://www.rsmeans.com/products/reference-books/methodologies-standards.

aspx (accessed February 20, 2017).

The Appraisal Foundation (TAF). 2012–2013. Uniform Standards of Professional Appraisal Practice. Washington, DC: TAF.

Urban and Regional Information Systems Association (URISA) and IAAO. 1999. GIS Guidelines for Assessors. Park

Ridge, IL: URISA; Chicago: IAAO.

Suggested Reading

Cunningham, K. 2007. “The Use of Lidar for Change Detection and Updating of the CAMA Database.” Journal of Prop-

erty Tax Assessment & Administration 4 (3): 5–12.

IAAO. 2005. Standard on Valuation of Personal Property. Kansas City: IAAO.

____. 2016. Standard on the Valuation of Properties Affected by Environmental Contamination. Kansas City: IAAO.

17

STANDARD ON MASS APPRAISAL OF REAL PROPERTY—2017

Assessment Standards of the International

Association of Assessing Officers

Guide to Assessment Standards

Standard on Assessment Appeal

Standard on Automated Valuation Models

Standard on Contracting for Assessment Services

Standard on Data Quality

Standard on Digital Cadastral Maps and Parcel Identifiers

Standard on Manual Cadastral Maps and Parcel Identifiers

Standard on Mass Appraisal of Real Property

Standard on Oversight Agency Responsibilities

Standard on Professional Development

Standard on Property Tax Policy

Standard on Public Relations

Standard on Ratio Studies

Standard on Valuation of Personal Property

Standard on Valuation of Property Affected by Environmental Contamination

Standard on Verification and Adjustment of Sales

To download the current approved version of any of the standards listed above, go to:

IAAO Technical Standards